| Film History | New Uncertainties – Austrian Documentary Cinema in the 1990s |

Traditionally also a place of new and rediscovered works, not only in terms of the films shown in competition, the Diagonale will once again offer two film historical programs in the scetion Film History for the upcoming edition which, by looking at the past, also allow conclusions to be drawn about the Austrian present.

Diagonale is pleased to announce the first of the two programs, including the selected films: Under the title New Uncertainties – Austrian Documentary Cinema in the 1990s, the festival will embark on a search for traces of domestic documentary filmmaking during that decade. The eleven films (nine documentaries and two innovative short films) employ a variety of formal approaches and will be presented in seven programs.

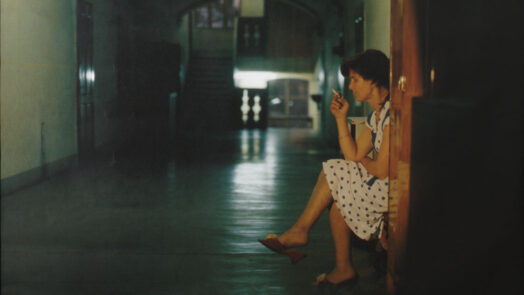

Postadresse: 2604 Schlöglmühl by Egon Humer © Prisma Film

“‘New Uncertainties’ looks back at the 1990s in Austria: a new beginning and disillusionment after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc combined with political and economic crises that continue to shape the country today. The documentary films of this period record these developments and question them. This filmmaking is characterized by a new diversity of forms that is critical of representation.” — Dominik Kamalzadeh & Claudia Slanar

NEW BEGINNING AND DISILLUSIONMENT

The special program shows how Austrian cinema dealt with the various developments of that time: from the aforementioned collapse of the Eastern Bloc to the Yugoslav Wars with their displacement and migration; from the definitive end of the Kreisky era to the rise of Jörg Haider and new forms of remembrance culture.

In Postadresse: 2640 Schlöglmühl (1990), Egon Humer examines the moral, political, and emotional consequences eight years after the closure of a paper factory that was considered one of the most important employers in the region. Amidst decaying buildings, abandoned factory halls, and the voices of those affected, one of the most remarkable social studies in Austrian cinema history emerges, in which powerlessness and oblivion are equally palpable. In his groundbreaking short film Knittelfeld – Stadt ohne Geschichte (Knittelfeld – City Without History, 1997), Gerhard Benedikt Friedl shows connections between the transformation of an entire city with the fate of one family. In the early 1990s, shopping centers and retail outlets fundamentally changed the face of this small Styrian town, while at the same time violence and crime unfolded in a family tragedy. Margareta Heinrich and Eduard Erne have opened up the dark chapter of Rechnitz 1945 with Totschweigen (Veil of Silence, 1994): around 180 Hungarian-Jewish forced laborers were victims of a mass murder in a field. Their graves are still being searched for today. Four decades after the end of the war, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, gaps in memory, silence, and the contradictory testimonies of the residents are documented.

In his intimate long-term observation Das Jahr nach Dayton (The Year After Dayton, 1997), Nikolaus Geyrhalter accompanies a handful of people as they rebuild their lives after the end of the Bosnian War: exhumations from mass graves, destroyed houses, and the daily struggle for normalcy reveal that after a catastrophe, no questions remain, only answers – incomplete and fragile. In Somewhere Else (1997), Barbara Albert portrays four young people who survived the war in Sarajevo in an equally impressive manner – four months after the end of the war, they describe their feelings during the siege of the city and their attempts not to lose hope for a better future. Draga Ljiljana (2000) by Nina Kusturica develops from a touching search for her childhood friend Ljiljana into a personal search for her own childhood, her past, and a homeland destroyed by war.

Finally, in Aufzeichnungen aus dem Tiefparterre (Drawings from the Basement, 2000), Rainer Frimmel documents the life of Viennese truck driver Peter Haindl from 1993 to 1999. Haindl reflects, laments, and politicizes in front of the camera, alternating between narcissistic poses and contrite self-analysis. Frimmel’s montage opens up a multi-layered portrait of the Austrian soul, in which everyday life, resentment, and self-irony collide.

The Diagonale would like to thank the Filmarchiv Austria, the ORF Archive and the Austrian Film Museum for their support.